February 22, 2021

In case you have ever tasted beer or whisky or consumed dark bread or a more exotic delicacy, such as the Finnish mämmi, you have also received a bunch of potentially beneficial phytochemicals in your body, according to a study we published recently from our academic work in a new journal, npj Science of Food. The common factor between these beverages and foods is malting, a food technological process which transforms not only whole grains into malt but also the compounds the grains contain.

Malting is a complicated process, which requires highly specialized facilities and long experience to yield material that is suitable for brewing a specific type of beer, for example. The process starts from drying the raw grain material: typically barley, but also other cereals are used, such as rye or wheat. Then, the grains are steeped in wet conditions to allow the grains to germinate. Once small rootlets have grown enough, after about six days, the germination process is stopped by heating the grains in an oven, which will give them a golden or dark brown colour, depending on the desired conditions. The malt must still undergo several steps, including extractions and mashing, before it becomes the final edible (or drinkable) product.

In our study, we received samples from different steps of the malting process from our collaborator, one of the largest malt producers in Europe. We analysed them with our nontargeted metabolomics platform and focused on phytochemicals, the proposed mediators of the beneficial health effects of plant foods. We already knew that whole grains are a rich source of phytochemicals, but we didn’t know exactly how rich and to what extent malting affects the bioactive compounds.

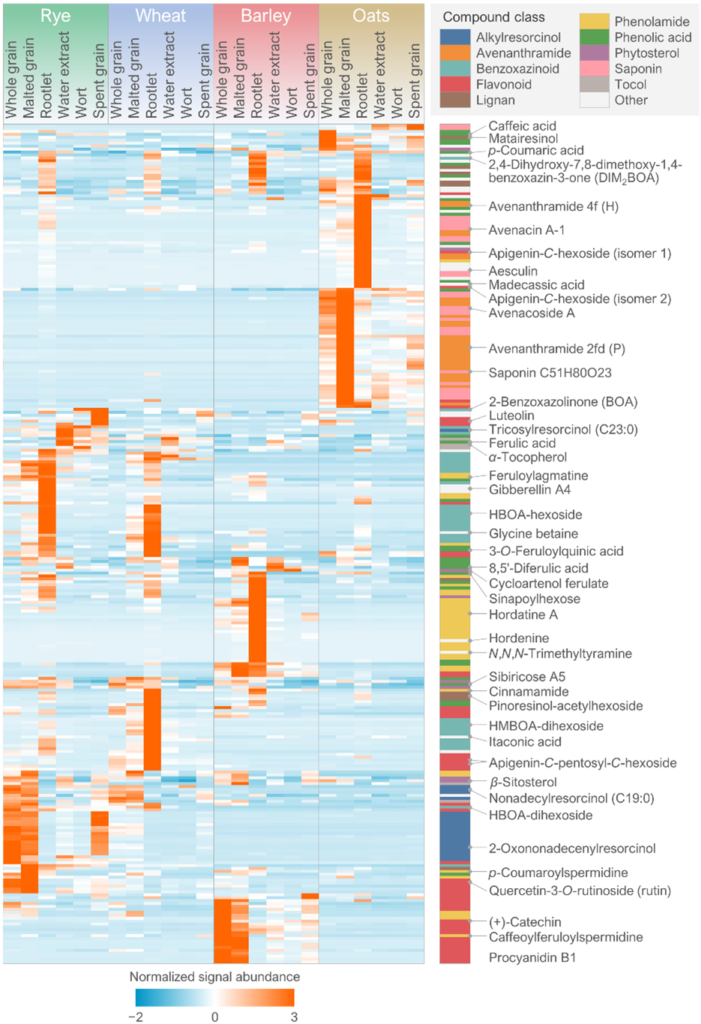

Our main finding from the massive dataset was that whole grains in general are a very rich source of phytochemicals, evidenced by the nearly 300 different phytochemical compounds found from the samples (see figure below). The actual number may be considerably higher, because a large portion of the signals detected in our study remained unknown, which is typical for a metabolomics study like this. Out of the cereal species, rye had the largest number of different phytochemicals (almost 200). Interestingly, malting not only increased the abundance of many phytochemicals but it also created new ones, especially in the rootlet samples. This is mainly because malting includes the germination process, which is when the grains come to life and start producing all kinds of molecules required for their growth.

This heatmap, compiled from all the analysed samples (columns) and all the 285 identified phytochemicals (rows), offers a glimpse of the multitude of phytochemicals present in just one type of plant food. Orange areas in the heatmap show increased phytochemical abundances in certain samples, which stem from the cereal species (highlighted at top) or from the malting process. Image: Koistinen et al.: Side-stream products of malting: a neglected source of phytochemicals. npj Science of Food, 2020. Published under Creative Commons BY 4.0

Since the human population is growing in a world struggling to provide food for everyone without compromising all other life on our planet, it is increasingly important to find new sustainable sources of nutritious food. The rootlet that appears during malting gets discarded and is currently sold to be used as animal feed. However, this part in particular has a high protein content, and according to our study, it is also an abundant source of phytochemicals. Why throw it away for inefficient use when we could consume it ourselves? It may be because the taste is somewhat unpleasant, although we didn’t get a chance to try ourselves. Some development, perhaps a fermentation process, is therefore needed before we can supplement food with this very potential material.

In the meanwhile, if you’ve never tried mämmi mentioned in the beginning, try it this year or make some yourself if it’s not available in the store (which is likely if you live outside Finland). It’s a dessert that tastes much better than it looks.

Read our open-access publication here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41538-020-00081-0

Example of a mämmi recipe: http://cookingfinland.blogspot.com/2011/04/mammi-traditional-finnish-porridge-or.html

Ville Koistinen

Afekta Technologies